Faith Ringgold was born in 1930 in Harlem to a working class family. She began to study art and education at the City College in New York in 1948. She is well known for her painted story quilts, which blur the line between "high art" and "craft" by combining painting, quilted fabric, and storytelling. She was influenced by the fabric she worked with at home with her mother, who was a fashion designer, and has used fabric in many of her artworks. Her work is in the permanent collection of many museums including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and other museums, mostly in New York City.

In 1963 she had her first solo exhibition with The American People Series. Heavy outlines and flat spaces of dark or saturated color were becoming Ringgold’s recognizable style in her paintings and what she termed as “super-realism.” Her paintings in this series were highly political and included images of social satire and confronted the racial tensions of the time and issues of tokenism associated with integration and the efforts of African Americans to “assimilate” into white society. Ringgold said that her objective with the series “was to make a statement about the Civil Rights movement and what was happening to black people at the time.” In her paintings The Flag is Bleeding, Die and U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power she portrays the shift from nonviolent civil rights advocacy to the violent confrontations that began to occur in the late 60s.

Ringgold continued to be political and social active and her work reflected her involvement. In 1970 she completed The Black Light Series that contained controversial images and text. In her painting Flag for the Moon, she comments expresses her anger over the billions of dollars spent to put a man on the moon while millions of Americans continue to live in poverty. Also, she comments on and questions the image of the American flag as a symbol of freedom and justice.

In 1972, during a visit to Amsterdam Ringgold observed a collection of Tibetan Buddhist paintings that were rendered on silk and hung on wooden dowels called thangkas. Ringgold adapted similar techniques within her own work. Also, as a child, she was taught to sew fabrics by her mother and drew upon the African American quilt-making tradition. Quilts in the African American slave community served various purposes: warmth, preserving memories and events, storytelling, and even as "message boards" for the Underground Railroad to guide slaves on their way north to freedom. Some techniques common to African-American quilts included patchwork and appliqué.

Through her work on fabric Ringgold confronted personal issues such as the death of her mother, her childhood in Harlem and her identity as an African American woman. She also incorporated handwritten text into her story quilts to create narratives dealing with themes of race and gender, such as, Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? where she explores the Aunt Jemima or “mammy” image in American popular culture and the French Collection, where she explores the race and gender within art history, particularly in Modern art.

Questions/issues to think about

Ringgold uses provocative language/imagery and depicts violence in her work – relating to the work and issues of Kara Walker – does this perpetuate negative stereotypes or criticize/critique?

How does the medium (particularly cloth/quilting) that Ringgold works with affect her narratives she creates?

Monday, March 31, 2008

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Shahzia Sikander

Born in Lahore, Pakistan in 1969, Shahzia Sikander is an artist who currently lives and works in New York City. Sikander acquired a Bachelor of Arts from the National College of Arts in Lahore where she learned the traditional practice of miniature painting. After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design’s Master of Fine Arts program in 1995, Sikander moved to New York City to pursue her artwork. In 2006, the MacArthur Foundation awarded Sikander with the great honor of the Young Global Leader Fellowship. The work of Sikander is full of loaded imagery, visually beautiful, and ambiguous.

Despite the efforts of her peers and advisers to dissuade Sikander from miniature painting, the artist chose to study the low art form in an act of defiance. Sikander once felt that the form was ‘too kitsch and [her] limited exposure was primarily through work produced for tourist consumption.’ Sikander views her work as a deconstruction of the miniature painting by showing through her painting style that tradition, ideas, and the universe at large are constantly in a state of flux. The use of line is constantly evolving in her work so that a subject in one painting can be realistic, but in another painting the subject will appear entirely different. Recently, the artist has experimented with other forms such as installation, animation, and photo realistic drawing. The prominent goal of the artist is to illustrate the constant changing nature of boundaries whether they are cultural, emotional, psychological, etc. The work reflects the ever changing because of the layering of paint or animation that is fluid and contradicting.

Sikander is able to move past post-colonial clichés expected of her by disrupting the viewer’s perception with unlike objects and ideas connecting to each other. Sikander views binary oppositions as creators of oppression and hierarchy. Instead of using binary opposition in her work, Sikander layers subjects or uses peculiar forms. The subjects in her paintings come from Muslim, Persian, Western, Islamic, Greek, and Roman tradition. Identity, culture, tradition, and the inner self become entities that are fluid and able to move through time and space. This theme resonates with the deconstruction of the miniature as something that is a tradition but also as something that can be reinvented. From the ‘Dissonance to Detour’ work, the fluidity and chaos of language is present. The interpretation of language is something non-concrete and layered. A political topic that Sikander purposefully engages with is feminism. By using certain symbols of feminine and masculine identities, stereotypes of feminine representation are questioned.

A common critique of Sikander’s work is the perpetuation of stereotypes of South Asia. This critique comes from the exoticism and sensuality of the work. The use of the miniature is also problematic because the origin is centered around an ethnicity. Sikander argues that her work has become a ‘spectacle with cultural definitions’ rather than a body of work. The artist wants to frustrate meaning, to blur the boundaries between preconceived notions, and to show the layers and fluxuation in life through her work. The body of work becomes political to viewers because of the ‘foreign’ elements and symbols within the pieces. Sikander contemplates why ‘people have the inability to see the conceptual in other forms.’ The ambiguity of Sikander’s work is the element that draws viewers to her work, and if one loses a sense of curiosity with a narrow perception the pieces become post-colonial clichés.

“I was shocked to learn of people's inability to see "the conceptual" in other forms, ones outside the rather recent, narrow parameters established by practices of the 1960s, I find miniature painting a very conceptual activity.”

“It is not a question of what kind of meaning the image is transmitting, but what kind of meaning the viewer is presenting.”

“I am not a spokesperson.”

“Deconstructing is not the act of dismantling but recognition of the fact that inherently nothing is solid or pure. “

(shahziasikander.com)

Question: Do you agree with the ideas of Sikander? Do you feel that her work can be conceptual, and that if we assume there is a specific political message we are being ethnocentric?

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

Chris Ofili Painted Figuratively

Chris Ofili is of Nigerian heritage but was born in Manchester, England in 1968. He is Roman Catholic. He received his BA in fine art from the Chelsea School of Art in London, and his MA in fine art from the Royal College of Art in London. He won the Turner prize in 1998, an annual prize presented to a British artist under 50 organized by the Tate Modern.

Radically different themes often cause divisions and conflict within individual paintings. He believes art should be unrestricted by cultural norms, and much of his work incorporates collage from pornographic magazines as well as elephant dung. Ofili's painting also references “blaxploitation” films and gangsta rap often to question racial and sexual stereotypes in a humorous way. His work among other themes, comments on British racism.

In 1992 he won a scholarship allowing him to travel to Zimbabwe where he studied cave paintings, from which he adopted the map-pinning technique. Ofili's use of elephant dung began in Africa when, dissatisfied with the paintings he was making there, he picked up some dried cow dung and stuck it onto one of his canvases. When he came back to Britain, he brought dung with him, and incorporated it in a performance art piece, in which he sat on the street with the dung on a sheet as if it were for sale.

His paintings are meant to be viewed both close up and far away, and he often incorporates pornographic collage that becomes evident as such only when the viewer comes near. The Holy Virgin Mary exemplifies this technique, placing female genitalia around the sacred figure. He wanted viewers to realize how sexually charged even the Western portrayals of the Virgin Mary are, especially in reference to a mother breastfeeding her child.

“Chris Ofili portrays the Virgin Mary as a rather exciting black with impressive eyes, a hint of breast upon which a piece of dung has been placed signifying nourishment, the color of darkness, a broad nose and a sensuousness not generally assumed when one sees the Eurocentirc version of Mother Mary” this review has been stated as “a product of sensitivity to black values and aesthetics” (from Amsterdam Magazine, a popular black magazine in New York).

In an interview, the artist asserts that his paintings are part of hip-hop culture, and states that his work operates on multiple levels and is open to interpretation. He explains his intention of transforming everyday `junk' and aspects of contemporary culture into thought-provoking images, noting the importance of his identity as a Londoner.

The Upper Room (2002)

The Upper Room is an installation of 13 paintings of rhesus macaque monkeys referencing the last supper. The room was built especially for this show. It was bought by the Tate Gallery in 2005 and caused controversy as Ofili was on the board of Tate trustees at the time of the purchase.

Each painting depicts a monkey based around a different color theme. The particular monkey represented is commonly used in medical testing because of its similarities in blood groups. Ofili has researched the traits of this an in many ways holds them higher than human beings, an ideal that clashes with scripture in Catholic tradition.

On Chris Ofili’s paintings:

“Their beauty is not about being one thing but about multiplicity—kitsch hangs out with sophistication, beauty plays with ugliness, and sacred clashes with the profane. Ofili deliberately spars with our prejudices and preconceptions to create extraordinary complex paintings that push past the point of excess.” (Stephen Snoddy, director of the Southampton Serpentine Gallery in London)

Good Interview!--Ofili's Glittering Icons - work of Chris Ofili at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, New York from Art in America, Jan, 2000, by Lynn Macritchie.

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1248/is_1_88/ai_58616908

In an interview, Chris Ofili once said that art can be constructed from anything and should be unrestricted by cultural norms. Do you agree/disagree and why?

How is Ofili’s use of racial stereotypes similar to that of Kara Walkers? Does the incorporation of religion make one more or less taboo than the other?

Radically different themes often cause divisions and conflict within individual paintings. He believes art should be unrestricted by cultural norms, and much of his work incorporates collage from pornographic magazines as well as elephant dung. Ofili's painting also references “blaxploitation” films and gangsta rap often to question racial and sexual stereotypes in a humorous way. His work among other themes, comments on British racism.

In 1992 he won a scholarship allowing him to travel to Zimbabwe where he studied cave paintings, from which he adopted the map-pinning technique. Ofili's use of elephant dung began in Africa when, dissatisfied with the paintings he was making there, he picked up some dried cow dung and stuck it onto one of his canvases. When he came back to Britain, he brought dung with him, and incorporated it in a performance art piece, in which he sat on the street with the dung on a sheet as if it were for sale.

His paintings are meant to be viewed both close up and far away, and he often incorporates pornographic collage that becomes evident as such only when the viewer comes near. The Holy Virgin Mary exemplifies this technique, placing female genitalia around the sacred figure. He wanted viewers to realize how sexually charged even the Western portrayals of the Virgin Mary are, especially in reference to a mother breastfeeding her child.

“Chris Ofili portrays the Virgin Mary as a rather exciting black with impressive eyes, a hint of breast upon which a piece of dung has been placed signifying nourishment, the color of darkness, a broad nose and a sensuousness not generally assumed when one sees the Eurocentirc version of Mother Mary” this review has been stated as “a product of sensitivity to black values and aesthetics” (from Amsterdam Magazine, a popular black magazine in New York).

In an interview, the artist asserts that his paintings are part of hip-hop culture, and states that his work operates on multiple levels and is open to interpretation. He explains his intention of transforming everyday `junk' and aspects of contemporary culture into thought-provoking images, noting the importance of his identity as a Londoner.

The Upper Room (2002)

The Upper Room is an installation of 13 paintings of rhesus macaque monkeys referencing the last supper. The room was built especially for this show. It was bought by the Tate Gallery in 2005 and caused controversy as Ofili was on the board of Tate trustees at the time of the purchase.

Each painting depicts a monkey based around a different color theme. The particular monkey represented is commonly used in medical testing because of its similarities in blood groups. Ofili has researched the traits of this an in many ways holds them higher than human beings, an ideal that clashes with scripture in Catholic tradition.

On Chris Ofili’s paintings:

“Their beauty is not about being one thing but about multiplicity—kitsch hangs out with sophistication, beauty plays with ugliness, and sacred clashes with the profane. Ofili deliberately spars with our prejudices and preconceptions to create extraordinary complex paintings that push past the point of excess.” (Stephen Snoddy, director of the Southampton Serpentine Gallery in London)

Good Interview!--Ofili's Glittering Icons - work of Chris Ofili at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, New York from Art in America, Jan, 2000, by Lynn Macritchie.

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1248/is_1_88/ai_58616908

In an interview, Chris Ofili once said that art can be constructed from anything and should be unrestricted by cultural norms. Do you agree/disagree and why?

How is Ofili’s use of racial stereotypes similar to that of Kara Walkers? Does the incorporation of religion make one more or less taboo than the other?

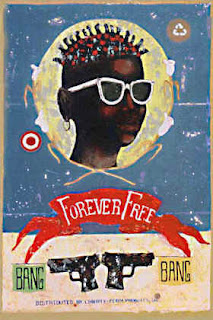

Michael Ray Charles

Michael Ray Charles was born in 1967 in Lafayette, Louisiana, and graduated from McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1985. In college, he studied advertising design and illustration, which I was originally very interested in. He, and I both, moved to painting as a preferred medium. Mr. Charles went on to receive his MFA degree from the University of Houston in 1993.

Just this past January, Black Issues in Higher Education magazine recognized Michael Ray Charles as one of ten scholars who are doing innovative research in their field of study, reaching out to shape the next generation of scholars, or committing themselves to working with communities and students of color.

His graphically styled paintings investigate racial stereotypes drawn from a history of American advertising, product packaging, billboards, radio jingles, and television commercials. Images such as Aunt Jemima and Uncle Tom, are incorporated into the artist’s work as he presents a contemporary impression of our world through the eyes and insights of a young black man. Charles draws comparisons between Sambo, Mammy, and minstrel images of an earlier era and contemporary mass-media portrayals of black youths, celebrities, and athletes (images he sees as a constant in the American subconscious). “Stereotypes have evolved,” he notes. “I’m trying to deal with present and past stereotypes in the context of today’s society.”

“In each of his paintings, notions of beauty, ugliness, nostalgia, and violence emerge and converge, reminding us that we cannot divorce ourselves from a past that has led us to where we are, who we have become, and how we are portrayed.”

His diptych, To See Or Not To See “After/ Before Black,” was inspired by a suite of lithographs produced in the 19th century by Currier and Ives. The printshop’s slogan boasts, a publisher of “Cheap and Popular Pictures” which included categories such as Sports, Hunting Scenes, Trains, Historical Portraits, and Religious Themes. Another category was Darktown, in which the many racist stereotypes of the day were depicted in humorous situations. Charles’ before-and-after paintings have a similar antique as these images and they modernize the sentiment with which we as viewers come to view these stereotypes of black people.

Charles believes that society treats black people one of two ways, as either entertainers or criminals. In an interview with Black Issues of Higher Education magazine he says, “I’ve always been searching for a better representation or understanding of what ‘blackness’ is, or was, or may be,” said Charles. “We are not yet getting master of fine arts degrees, and having galleries, and becoming patrons, and doing the things that are on the A-list of creative cultural production. That’s a major challenge to overcome.”

Sorry this posting is a bit late, here some questions to consider:

1. How does Charles' use text and color convey the idea of "freedom" and how does that relate to what he is trying to achieve with his work?

2. By using powerful, recognizable imagery, such as Sambo, is Charles critiquing or perpetuating a stereotype?

and 3. How would you view the work if you did not know who had painted it?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)